The latest news for New Zealand Landlords and Tenants

What is the ‘no cause clause’ and why is it so problematic?

Saying goodbye to no cause terminations is a very real possibility reading over the Residential Tenancies Amendment Bill. A Bill that aims to modernise the 1986 Residential Tenancies Act, this particular “no cause clause” is proving to be a little problematic. We take a closer look and ask, why?

If you’re a New Zealand landlord you may or may not know that no cause terminations are currently within your rights under the RTA. This is when a tenancy is terminated by the landlord with no reason or cause given.

Obviously, it’s more than a matter of picking up the phone and telling your tenant “Hello, it’s time to go!”. They must be in a periodic tenancy, not a fixed term, and you must provide the correct 90 days’ notice. But other than that, you currently can terminate a tenancy without giving a reason. The Residential Tenancies Amendment Bill wants to change this, however, to the following;

Two main reasons are given for this particular change:

- The first is that tenants will know why their tenancy is ending and know that a justified reason exists.

- The second is that it will provide tenants with more security in their living situation.

While this is awesome for tenants, not all landlords are convinced that the no cause clause is an issue in the first place. We take a look at some of the info available around this.

How much of an issue are no-cause terminations?

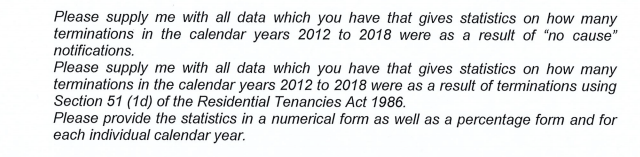

An Official Information Act request was submitted to MBIE on 14 August 2019 stating the following;

This request for data to back up the RTA amendment on no-cause terminations was declined.

The main reason for this was a lack of records:

“…there is no record of decisions about each time a ‘no cause’ termination has been used that can be analysed for insights about their frequency or the situations where they are generally used.”

Claire Leadbetter, Manager, Tenures and Housing Quality

Currently, a no cause termination can only be challenged by tenants if it is in breach of the tenancy agreement, or is issued in retaliation. Because of this, the Tenancy Tribunal records do not show the number of times this type of termination was used and why.

So, what research is the no cause clause based on?

The response to the OIA request mentioned above went on to say that research on the no cause clause was ‘limited to surveys of tenants and landlords.’ These surveys focus on their personal experiences with no-cause terminations, rather than using actual data.

The only statistics provided are from the New Zealand Property Investors Federation. President Andrew King is quoted as saying only about 3 per cent of his association’s members’ tenants were given a 90-day notice in a typical year.

Removing the use of no cause terminations means landlords will need to have a justifiable reason to end a tenancy. Some of these reasons could include:

- anti-social or illegal behaviour from the tenant

- 3 weeks of rent arrears

- the landlord wanting a family member or themselves to move in.

There are other reasons that you can read more on in the RTA Bill here.

For many landlords, this change implies that there is a current issue with the way no cause terminations are used. However, the lack of stats and reliance on subjective surveys means it is difficult to measure this at all. One thing we can measure though is how many people rent in New Zealand vs own.

Around 1 in 3 Kiwi households rent and this has been on an upwards rise since the early 2000s. As the RTA amendments aim to respond to this shift in the market and provide tenants with more security, the no cause clause could be seen as justified from this perspective.

Remember, landlords will still be able to terminate a tenancy and provide 90 days’ notice if this change goes ahead. The only difference is that a reason will need to be given, and the RTA will specify which reasons are justified.

Arguments against the no cause clause

In their arguments against this change, landlords and property investors often put forward a worst-case scenario that follows the ‘neighbours from hell’ narrative.

‘Susan and Geoff are pillars of the community, and have lived on their quiet street for years. They work hard and pay their taxes, and their rates. What if someone rowdy moves in next door and has parties? What if this person plays music at 1am, parks on the grass verge, and brings their once idyllic suburban paradise into disrepute?!’

Again, this argument is based on no research and is not quantifiable. So how much of an issue would these ‘neighbours from hell’ be if a landlord had to provide a reason to terminate their tenancy? Scenarios like this are a real possibility. But are they a valid enough reason to not go ahead with an end to no-cause terminations?

No cause terminations, NOT no cause evictions

The language being used to talk about this type of end to a tenancy has changed to become more inflammatory. This is another point landlords have made as the debate around no cause terminations receives more media coverage. The use of the word eviction, in particular, has been criticised.

“Contrary to widespread belief, a landlord cannot evict a tenant. ‘Eviction’ sounds great in the shock-horror media stories, but no residential landlord actually has the power to evict.”

Landlords.co.nz

Evictions are a long process that involves the District Court and Police. They are different from a no cause termination that ends a tenancy with no reason. However, the use of this word tells a different story. One where landlords unfairly exercise their power to kick out tenants.

This is where it’s important to remember what no cause terminations are. They are ending a tenancy with no reason given and they require a 90 day notice period. They are not evictions.

Why no cause terminations are a landlord’s last resort

On one hand, commentators are saying that landlords only care about money. If this is the case, a no cause termination wouldn’t be their first choice of action.

Ending a tenancy early with no reason might seem like a simple decision, but landlords do run the risk of losing out on rental income.

If money is the only priority in mind, why would they look to end a tenancy early for no good reason, and lose out on rental income? Aren’t they looking to squeeze every last dollar out of the renting population? Organise a move-out that collides perfectly with the move-in? One where the departing tenant can’t even close the back door before the new tenant has pulled into the driveway?

If a landlord issues a 90 day no cause termination, there’s a good chance that their house will be empty for a few days or even a few weeks. This all adds up. And some landlords say it’s exactly why they wouldn’t just terminate a tenancy with no actual cause. They say more than likely, there is a cause. However, no cause terminations avoid arguments and protect landlords from false promises of improvement that often just delay a termination process.

The no cause clause is one of many amendments currently being considered under the RTA Bill. While it intends to provide tenants with more security, not all landlords agree that it achieves what it intends to.

With another amendment aiming to change fixed-term tenancies, some landlords think this Bill will only make it harder for landlords to get rid of difficult tenants.

Article: What happens when my fixed-term becomes a periodic tenancy?